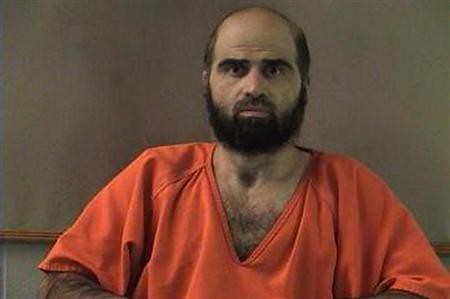

Nidal Hassan is going on trial for the killing of 13 people at a military base in Fort Hood, Texas., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Nidal Hasan convicted of Fort Hood killings

By Billy Kenber, Updated: Friday, August 23, 4:43 PM

Nidal Malik Hasan faces a possible death sentence after being found guilty Friday of killing 13 people and wounding dozens more when he opened fire at the Fort Hood Army post in Texas in November 2009.

Hasan, 42, a U.S.-born Muslim who acted as his own attorney, was convicted of 13 charges of premeditated murder and 32 of attempted murder by a panel of senior officers after almost seven hours of deliberations.

He stared at the panel’s president, a female colonel, as she read the verdict, but he showed no reaction, according to news agencies. Several survivors of the attack and relatives of those killed were in court, and some began to cry after Hasan and the panel had left the room.

The case will now move to a sentencing phase, during which more witnesses may be called and Hasan could testify before a punishment is handed down.

The unanimous verdict brings proceedings a step closer to ending one of the most painful chapters in recent U.S. military history. The FBI and Defense Department have both received criticism for failing to spot warning signs that Hasan had become radicalized, and survivors have accused the government of abandoning them and depriving them of financial benefits.

Hasan, who was paralyzed from the chest down and confined to a wheelchair after being shot by an Army civilian police officer while being apprehended, admitted responsibility for the shooting at the start of the trial, saying he had “switched sides.”

Aside from a brief opening statement and a few questions of prosecution witnesses, the military psychiatrist showed little interest in mounting a defense. Hasan, who was prohibited by military law from entering a guilty plea, declined to call any witnesses, testify himself or give a closing argument.

At a pretrial hearing, the judge, Col. Tara Osborn, ruled that Hasan could not defend himself by arguing that he carried out the killings to protect Taliban leaders in Afghanistan.

Instead, the defendant chose to make his case to the public through a series of communiques and authorized leaks to newspapers, arguing that he was waging jihad because of the United States’ “illegal and immoral aggression against Muslims” in Iraq and Afghanistan. In another document, it emerged he had told a mental-health panel that “if I died by lethal injection, I would still be a martyr.”

During the court-martial, Osborn refused a request by Hasan’s three standby lawyers to limit their role because they believed the defendant was trying to secure a death sentence.

Experts said that in spite of Hasan’s apparent desire to be executed, it will be years before a potential death sentence could be carried out.

Under the military’s justice system, there are several automatic appeal stages, during which lawyers are likely to be appointed to represent Hasan, regardless of the defendant’s wishes.

After a sentence is handed down, the court’s records and findings will have to be reviewed and approved by a military official known as the convening authority.

The case will then enter the appellate phase, going before the appeals courts for the Army and the armed forces. The case can be appealed to the Supreme Court. Finally, the president must sign off on the death sentence. The last time an active-duty soldier was executed was in 1961.

Eugene R. Fidell, who teaches military justice at Yale Law School, said he expected the appeals process to take several years. “It’s most likely to be the next president that’s going to have to make the final decision,” he said.

Greg Rinckey, a former U.S. Army Judge Advocate General’s Corps attorney, said the appeals courts were highly unlikely to allow Hasan to represent himself and that his appointed attorney could lodge a number of challenges.

“Part of defense strategy in this case will be delays . . . [and] I think they’re going to file mental-health issues, whether he had the capacity to stand trial, ineffective assistance of counsel,” Rinckey said.

The military trial, which lasted 2 1 / 2 weeks, took place almost four years after the mass shooting because of legal delays, with Hasan twice dismissing his legal team. There was also protracted argument before he won the right to keep his beard.

During hearings, held at a courtroom a few miles from the site of the shooting on the sprawling Texas Army post, the defendant declined the opportunity to cross-examine some of his victims.

Hasan had been due to deploy to Afghanistan within a few weeks of the attack, and prosecutors presented evidence of his meticulous planning. The Army major and psychiatrist chose the most high-tech, high-capacity weapon available at a gun store in Killeen, Tex., and trained himself at a local firing range before giving away some of his belongings on the day of the shooting.

Shortly after 1 p.m. on Nov. 5, 2009, Hasan walked into Fort Hood’s Soldier Readiness Processing Center with two guns, shouted “Allahu akbar!” meaning “God is great,” and opened fire, the court was told.

His victims were almost all soldiers who were waiting for blood testing. The sole civilian killed was shot as he attempted to tackle Hasan using a chair, according to testimony.

Hasan’s rampage exposed a number of failings by the Defense Department, which a Pentagon report concluded was unprepared for internal threats, and by the FBI. On one occasion, Hasan gave a presentation to senior Army doctors in which he discussed Islam and suicide bombers and warned that Muslims should be allowed to leave the armed forces as conscientious objectors to avoid “adverse events.”

The FBI was also aware that the 42-year-old major had exchanged 18 e-mails with Anwar al-Awlaki, a radical U.S.-born Islamic cleric who was a leading figure in al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula before he was killed by a U.S. drone strike in 2011. However, the e-mails were dismissed as legitimate research, and the Defense Department was not informed.

Survivors have alleged that warnings were ignored because of “political correctness,” and many have also bitterly contested a decision to categorize the mass shooting as “workplace violence” rather than a terrorist attack.

More than 130 victims of the shooting and their family members have joined a lawsuit seeking damages and enhanced benefits from the U.S. government.

Reacting to Friday’s verdict, Sen. John Cornyn (R-Tex.) said in a statement: “The victims and families have had to wait for far too long for today’s decision, but I hope they can take some relief in today’s outcome as they and the entire Fort Hood community continues to grieve.”

He added: “We must turn our attention to ensuring that the victims of this horrible tragedy and their families receive the full honors and benefits bestowed upon soldiers who are wounded or killed in overseas combat zones.”

Texas Gov. Rick Perry (R) said: “Nidal Hasan’s cowardly attack on our military was a deliberate act of terror against our country. This guilty verdict affirms we are a nation of laws, honors the victims of this heinous act, and proves that, even in the face of unspeakable tragedy, we will never waver from the core principles for which they gave their lives: freedom, liberty and democracy.”

During the sentencing phase, the prosecution and defense can present evidence on the impact of the crime and any mitigating circumstances. Three-quarters of the military jury must vote to approve a prison term of more than 10 years; a unanimous decision is required for the death penalty.

No comments:

Post a Comment